Forty-six years after the fact it sometimes seems as if Nov. 22, 1963, were only 26 seconds long. That is roughly the length of the Zapruder film, the home movie that captured the shooting of President John F. Kennedy better than any other known footage.

But that Nov. 22 had 24 hours like any other day, and to get a true sense of what the assassination did to the country requires looking at the whole day, as well as the several event-filled ones that followed, in detail.

“The Lost JFK Tapes: The Assassination,” Monday night on the National Geographic Channel, does just that, creating a moment-by-moment account from numerous film and photographic sources, few of them familiar in the way the Zapruder film is. The program avoids the usual documentary intrusions: It has no present-day interviews with former Secret Service agents or functionaries, sharing their memories; no interpretive commentary from history professors. And it is mesmerizing.

Ron Frank, the producer and editor, shows a fine eye for small touches that say a lot. That morning in Fort Worth, Kennedy’s first stop before proceeding to Dallas, Raymond E. Buck, president of the Chamber of Commerce, gave him a Texas-size hat, which Kennedy, strangely, declined to don for the assembled audience. “I’ll put it on in the White House on Monday,” Kennedy says. Instead, that Monday he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Mr. Frank also knows what not to use. The often-seen clip of Walter Cronkite trying to hold his emotions in check is nowhere to be found. Instead the focus is on local journalists scrambling to get the facts and make sense of them.

“I’d like to speak here for the city of Dallas,” Jay Watson, program director of WFAA-TV in Dallas, says in a touchingly human vignette once Kennedy’s death is confirmed. “We are ashamed at the moment.”

It is also Mr. Watson who is shown soon after that interviewing a man who has brought some film he shot to the station. It is Abraham Zapruder.

The program is full of details like that. We see the seeds of what would become the Kennedy assassination oeuvre, as it were, being planted in the first hours. Almost immediately after Lee Harvey Oswald is shot by Jack Ruby, a newsman is heard speculating that Oswald was killed to silence him.

Only three people died in those long-ago events — the president, Oswald and a Dallas police officer named J. D. Tippit — but as this program makes clear, it is not spurious to compare the assassination and its aftermath to a more recent, much deadlier day, Sept. 11, 2001. Each had the same feeling that unimaginable events were unfolding faster than they could be comprehended, and the same sense that the world had changed in an eye blink.

If people under a certain age wonder why the Kennedy assassination continues to be such a preoccupation for so many, the hundreds of traumatized faces that flit through this program should make it clear.

BY DAVID HINCKLEY

National Geographic performs an impressive television and historical feat Monday with "The Lost JFK Tapes: The Assassination." It reconstructs President John F. Kennedy's 1963 killing with two well-told, fast-paced hours pieced together from contemporary TV coverage.

Forty-six years and a day after Kennedy's death, the event never has or will require embellishment. The more straightforward the narration, the greater the shock and horror.

National Geographic has promoted this fascinating documentary with some mild hype, like "Rarely seen news footage!"

But the producers realize that what brings back the day for those who were alive, or helps explain it to those who weren't, is the story itself.

On Friday, Nov. 22, Kennedy was killed. Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested. Two days later, Oswald was killed, leaving much of America dazed and disoriented. National Geographic doesn't clutter this chronological narrative with ominous voice-overs or rhetorical flourishes. It lets viewers watch and listen as reporters and citizens try to sort things out.

Today, with the Internet and 2-4/7 connectivity, that would be a very different process. Every random passing notion or rumor, the parts that were true and the many that were not, would have bombarded the world.

The result, very likely, would have been a different kind of chaos, compacted and more intense

Through modern eyes, then, the 1963 reaction feels almost like slow motion. That doesn't make it less devastating or powerful.

Drawing on the archives of the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, National Geographic dusts off black-and-white clips of local Dallas TV anchors and reporters first reporting how well the President's trip is going, how the crowd seems so peaceful and friendly.

Then shots are heard, the presidential limo speeds to the hospital and the reporters turn to stunned people who don't know what happened, except they sense it's bad.

Then shots are heard, the presidential limo speeds to the hospital and the reporters turn to stunned people who don't know what happened, except they sense it's bad.

Back in the studio, anchors puff on cigarettes as they try to put the story together. After Oswald is arrested, they have trouble getting his name right.

The Dallas police talk about their strict security as they parade Oswald for photo-ops. He says he didn't kill anyone, that he's a "patsy." We see Jack Ruby inside the station. Outsiders think he's another Secret Service agent.

Then he shoots Oswald, on live TV, and the rest of the country has lost even the consolation of pausing to mourn.

None of this story is new, and National Geographic steers away from controversies, like Oswald's guilt. This thorough, understated approach enables the channel to do a very good job of evoking a very bad week.

The 46th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy brought out some of the usual suspects, with the Discovery Channel last night asking "Did the Mob Kill " and following up with a documentary, "JFK: The Ruby Connection," that looked into whether Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald might have known his killer before Jack Ruby pulled out that gun. (They'll re-air at 9 and 10 p.m. Dec. 3 if you're interested.)

One night apparently isn't enough, though, so tonight at 9, the National Geographic Channel has "The Lost Tapes: The Assassination."

"Lost" might not be the best way to describe most of the footage in the special, a compilation of news footage, audio reports and recordings and some home movies from the period before and after Kennedy's death.

National Geo's own press materials say most of it, kept first at a Dallas/Fort Worth TV station and later archived at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dallas' Dealey Plaza, has been "rarely seen," without suggesting that that might not have been such a bad thing.

So I'll say it.

If you're old enough to remember the assassination, you have your own memories of that day, and if not, what you know has probably been shaped by old clips of people like Walter Cronkite reporting on it.

Too much of the two hours of "Lost Tapes" consists of footage from local TV anchors and reporters in Dallas, behaving the way people who weren't on Cronkite's level often did, and still do: speculating on what they don't actually know, providing flowery but useless commentary and interviewing people on the street about their feelings.

That said, the clear embarrassment felt by all that such a thing had occurred in Dallas makes for an interesting sidelight. There's also some footage at the beginning of Kennedy artfully avoiding being seen in a cowboy hat that should probably be required viewing for future candidates.

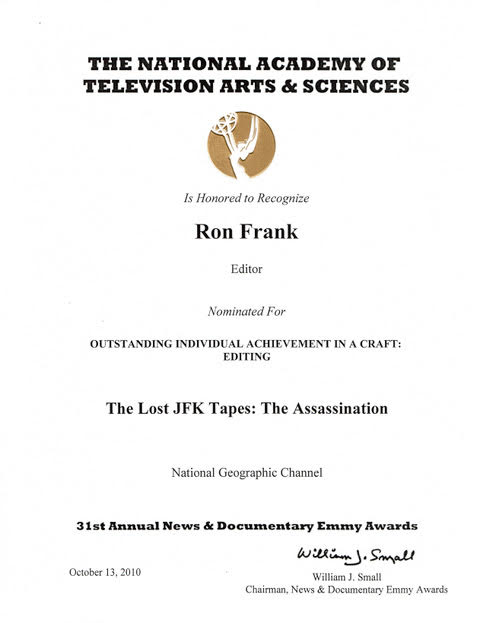

Emmy Nomination